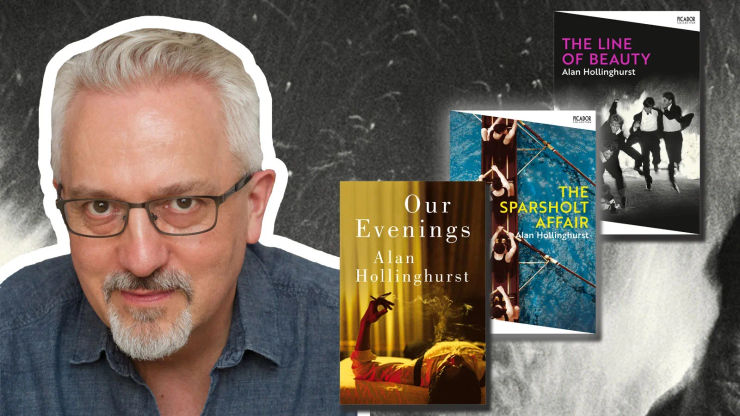

Alan Hollinghurst on writing The Line of Beauty

Alan Hollinghurst takes us through the writing process of The Line of Beauty, including the inspiration that Henry James provided for his writing style.

Originally published in The Guardian, 5 August 2011

My first novel, The Swimming-Pool Library, came out in 1988 and was set in 1983 – a five-year gap that covered the time of its composition, and in which the world the novel described changed dramatically. I began writing it on 1 January 1984, and it was intended to be strictly contemporary, though it also attempted to sketch in, through the diaries of an eighty-three-year-old man, a life that was as long as the century. In the summer of 1984, a close friend of mine developed a puzzling inability to heal or recover from minor ailments, and by early November he was dead.

By the time I was completing the book, in the summer of 1987, thousands of people were dead and dying of the same condition, and I, infinitely more trivially, was faced with an artistic problem. Should I adjust my depiction of the gay world to reflect what was happening? Should I add a dark update to its episodes from gay history? For various reasons, of both taste and technique, I decided to close the narrative in the late summer of 1983; but any reader in the late '80s and onwards would see that the young narrator's heedless present day had become historical in ways that he, and I, could never have predicted.

I went on to write two novels which, though touched by the AIDS crisis in different ways, didn't address it directly. This was partly resistance to a certain expectation that a gay writer would treat this urgent subject, but more because I couldn't see a way to do it that satisfied me artistically. Or perhaps I should just say that the books that accumulated and began to cohere in my mind and my notebooks were not ‘Aids novels'.

There are many things I don't understand about where my novels ‘come from'. I seem always to begin with the apprehension of details, as if, among objects in a commonplace view, one or two had begun to glow or resonate with imaginative potential. I want to describe life as it is, or was, but to give it an order I might loosely call poetic – a matter of rhythm, echoes, form as an agent of irony, an attempt to create a pervasive harmony through the narrative voice. There will be a narrative germ at or near the start (as it might be, ‘Tell story of Thatcher boom years from the inside'), but the shaping of the story comes last in the planning, and it's only when I've got that clear that I'll actually start writing (though by that stage I will probably have hundreds of pages of notes, thousands of accumulated details to be worked in).

In the case of The Line of Beauty, the narrative germ was accompanied by a dreamlike perspective of Kensington Park Gardens, a street that, when I first lived in London in 1981, I walked along several times a week on my way to swim at a local baths, and whose imposing houses, rather scruffier then than now, made me wonder about the lives led in them – it was all a part of my romantic sense of London as a scene of infinite possibilities, both real and fictional.

The novel opens in the late summer of 1983, just when my first book closed, and I must have felt I could at last address the upheavals, not only of Aids but of the whole of British society, that occurred over the following years. In The Swimming-Pool Library, the general election of 1983 had gone unremarked by the self-absorbed young narrator, but the new book was to be framed by the elections of 1983 and 1987, and to have an ambitious Tory MP as a leading character. It would not, however, be a panoramic public novel, but an intimate and peculiar personal history, of the kind I have always liked to write. My whole instinct was to work by irony and to make the world of money and power that young Nick Guest is drawn to absorb him and then expel him, as if from some phoney paradise. Nick was to be an unpolitical person in an age reconfigured by a political revolution.

The uneasy accommodations of a corruptible young aesthete to an ambiguous social world might have resonances too with the turn-of-the-century novels of Henry James, with their moneyed but morally seedy milieux. James was my own obsession at the time, and I worked him in various ways, also taking up the Jamesian challenge of narrating a large-scale novel in the third person entirely from the point of view of one character. Of course, I did many things that would have horrified the Master but were not I hope inconsistent with paying homage to him.

The Line of Beauty

The Line of Beauty is Alan Hollinghurst's Man Booker Prize-winning masterpiece. It is a novel that defines a decade, exploring with peerless style a young man's collision with his own desires, and with a world he can never truly belong to.