Qais Akbar Omar on writing and the real Afghanistan

Qais Akbar Omar, author of A Fort of Nine Towers, writes a letter to his readers.

Dear Reader:

My name is Qais Akbar Omar. I am an Afghan, a Muslim, a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed, peace be upon him, a carpet maker, a journalist, a boxer who has enjoyed breaking many noses, and “Qais, the Cruel Kite Cutter.” I just turned 30 years old, and am the author of A Fort of Nine Towers.

For centuries, until the time of my grandfather, my family were herders. We owned thousands of sheep and camels, and bought and sold carpets in bazaars all over Afghanistan. But no one in my family had ever actually woven a carpet until I did. That was during the time of the Taliban, when we had no other way to survive.

When I started writing A Fort of Nine Towers, I noticed how words are like knots in a carpet. One connects to the next until several make a thought, the way knots make a pattern. As I wrote about how I had lived with my family in my grandfather’s large compound along with nearly fifty of my immediate relatives, I realized that the pattern I was weaving with words was my family. The pattern changed as war blasted its front lines across our neighbourhood and tore it apart; our family was forced to flee to the Qala-e-Norborja, the Fort of Nine Towers, on the far side of Kabul.

It changed again. My father decided we had no choice but to escape to a neighboring country. He led us on a journey across northern Afghanistan trying to find a way out. For a time we lived in a tent in the middle of nowhere, then took shelter in the caves behind one of the Buddhas of Bamyan, which are no more. And for a while we traveled as nomads with Kuchi herders who are our distant relatives. All those twists in our lives got woven into my writing.

When people outside Afghanistan hear its name, they instantly think of war, bloodshed, destruction, violations of human rights, poppy growers, Mujahedin, warlords and the Taliban. All that does exist here, but sadly they are the only things that most people know about us.

They have never had the chance to stand in my grandfather’s large courtyard filled with his apple trees, rose bushes, and fragrant with the scent of grass, wood fires and kebab. They never sat there with my many cousins and me, in spring or summer in a tucked-away spot, as he recited poems by Rumi, Hafiz, Omar Khayyam, and told us tales of our history. They never spent an afternoon in autumn or winter gathered around a wood stove with Grandfather while he talked with his friends about poetry, literature, the environment, and the political situation in Afghanistan, while his volumes of poetry, Afghan History, and complete works of Sigmund Freud made a wall behind him.

Few outsiders really know about our deeply held personal values that are rooted in our families, customs, pride, honesty, and the obligation to decency that is instilled in the heart of Afghans from earliest childhood.

‘I want them to understand how someone like me came of age, getting what formal education I could when schools were open, and teaching myself what I needed to survive. I want them to know that from Grandfather I inherited a love of reading . . .’

Over the past four decades, many books about Afghanistan have been written – mostly by foreigners – but none have explained how Afghanistan has held itself together, from the Russian occupation, through years of brutal civil war, to the rise and fall of the Taliban, and the arrival of the American troops.

I wrote A Fort of Nine Towers for many reasons. Partly, I was trying to chase away the demons who haunt my dreams. Partly, it was a way of holding on to people I have lost. And partly I wanted to tell people from other countries some things about Afghanistan that they do not know.

I want them to understand how someone like me came of age, getting what formal education I could when schools were open, and teaching myself what I needed to survive. I want them to know that from Grandfather I inherited a love of reading, from our nomad cousins I learned to revere the beauty of nature, and with guidance from a deeply spiritual deaf-mute Turkmen woman, I discovered the art of carpet weaving that has become my life’s work.

With the end of the Taliban, I completed my university education, and taught myself English, so I could work with the flood of foreigners pouring into Afghanistan. I was eventually hired as a wool and carpet specialist by a number of international organizations. In 2007, I accepted an invitation to visit the University of Colorado to look for ways to wash carpets in Afghanistan without using environmentally destructive chemicals. Briefly, I made contact with the world beyond Afghanistan and saw how little they really knew about us.

That same year, I began writing an account of my early years that became A Fort of Nine Towers.

Everyone in my family is a story teller. Really, all Afghans are story tellers, but my mother is one of the best. As I wrote A Fort of Nine Towers, I tried to keep all that she had told me in mind.

Now that it is written, I feel that this carpet of words, A Fort of Nine Towers, does not really belong to me, but to my family. It belongs to my father, who is a high school physics teacher, and my mother, who used to be a banker and now helps people caught in natural disasters. It belongs to my five sisters and to my brother as they make their way in the world, dealing in their own ways with their own memories of what we endured as a family and how we survived.

Now I offer it to you, the most complex and difficult carpet I have ever woven: A Fort of Nine Towers.

Respectfully,

Qais Akbar Omar

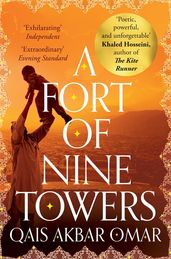

A Fort of Nine Towers

by Qais Akbar Omar

Qais Akbar Omar was eleven when a brutal civil war engulfed Kabul. For Qais, it brought an abrupt end to a childhood filled with kites and cousins in his grandfather's garden: one of the most convulsive decades in Afghan history had begun. Ahead lay the rise of the Taliban, and, in 2001, the arrival of international forces.

A Fort of Nine Towers is the story of Qais, his family and their determination to survive these upheavals as they were buffeted from one part of Afghanistan to the next. Drawing strength from each other, and their culture and faith, they sought refuge for a time in the Buddha caves of Bamyan, and later with a caravan of Kuchi nomads. When they eventually returned to Kabul, it became clear that their trials were just beginning.