In praise of short books

In this era of near-constant distraction, the promise of spending an hour or two with a book, rather than several days or weeks, can be attractive – but to say that was all there is to it would be selling short books, well, short, argues our website editor.

With the success of titles like Clare Keegan’s Small Things Like These and Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Open Water, it feels like appreciation for short books has, in contrast to their page count, really grown in recent years. In our age of dwindling attention spans, a short read can feel less daunting, something we can see ourselves actually finishing. And on the other end of the scale, if you're a big reader who likes to set yourself an annual target, you can, to be blunt, pack more books in when they’re only two hundred pages long. But authors don't tend to write in a certain form just because it's popular, and the reading public wouldn't take to these books in such numbers if they weren't also really good. So what is it that makes short books so appealing, for both creator and reader?

I love a long read. I love the space it gives the author to be both expansive and precise. The themes, ideas, geography, cast of characters: everything can be on a grand scale and simultaneously intricate and detailed. Nathan Hill’s Wellness, for example, which I read earlier this year, is an era-spanning portrait of America and also of a single relationship, and of the two people within and without it. With long form writing, the author has the time and words to construct a fully-formed world around us. This can be particularly effective in science-fiction, fantasy and historical fiction, the level of detail making the unfamiliar and the alien feel tangible and real. With Ken Follett, you're back in the twelfth century. With Adrian Tchaikovsky you're placed down on a hostile, terraformed planet. Long books allow us to really get to know the characters and invest in their lives, hours of our time dedicated to theirs. We cry at A Little Life because we’ve grown with the characters over four decades and 752 pages. We care about Middlemarch’s Dorothea because we feel we know her.

Short books are no less affecting, just in a different way; a pinprick to a long book's rumbling ache. They're glimpses that reveal bigger truths, carefully cropped images that adjust our focus on the wider picture.

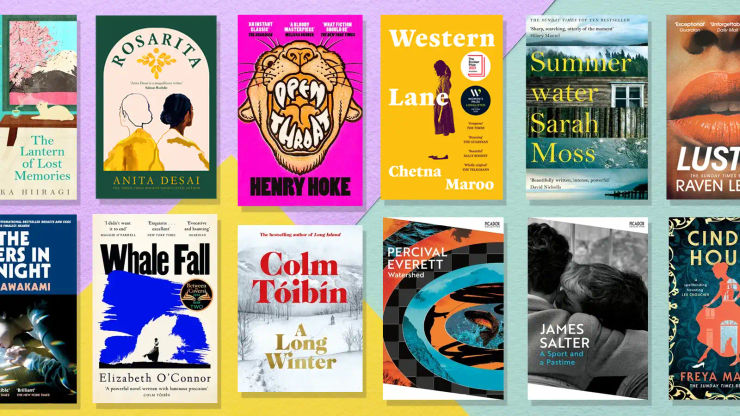

There's a great deal of skill involved in creating something meaningful and satisfying within limited parameters. When you've no room to expand and elaborate, a lot often lies in what isn’t said, and it takes a great writer to make this work. Chetna Maroo is one such writer. Her Booker shortlisted debut Western Lane (176 pages) “unfolds in silences” says the Guardian, “and dares to leave much unsaid.” Another debut, Elizabeth O'Connor’s Whale Fall (224 pages), has not an inch of fat on its haunting, evocative bones, its restrained precision – in both style and word count – reflecting the confines and restriction of its island setting, producing in the reader the same yearning claustrophobia felt by its young protagonist.

If my admiration for long books suggests that comprehensive world-building isn’t possible in fewer than 500 pages, then This Is How You Lose the Time War is the counterargument. This slice of science fiction comes in at 208 pages and submerges the reader in its time-travelling chaos by tossing them into the middle of it and leaving them to gradually work out what’s going on. There’s no exposition, no narrator. It’s thrilling, and lyrical, and I wouldn’t want 600 pages of it.

‘This is, I think, one of the real wonders of a short book: it can do things with form, structure, pace and indeed content that have a profound effect on the reader but which simply wouldn’t work over a greater number of pages.’

This is, I think, one of the real wonders of a short book: it can do things with form, structure, pace and content that have a profound effect on the reader but which simply wouldn’t work over a greater number of pages.

Henry Hoke’s Open Throat (176 pages) is narrated by a queer and dangerously hungry mountain lion living in the Hollywood Hills and its brevity is part of what makes it come off – what could stretch credulity in other hands is, in Hoke’s, a blinding fever dream of a novel.

Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From (144 pages), a frightening, moving dystopian vision of a familiar world overwhelmed by climate change, is written in generously spaced one and two sentence chunks, each a haunting, poetic polaroid from the end of the world. The effect is akin to a kind of flipbook, each line break urging you forward, each small moment driving you to the next. In a longer book this could become exhausting, the pace impossible to sustain. Here, it creates a sense of urgency even in the book’s quiet moments, befitting the dangerous and unstable world we travel through.

Hanna Bervoets’ We Had To Remove This Post (144 pages), translated by Emma Rault, is set in the world of online content moderation, and explores the effects of spending all day looking at the worst of the internet. It’s a short, sharp, shock of a book and it needs to be: we can’t be allowed the time to start anticipating the next appalling event, for Kayleigh and her colleagues’ behaviour to become normalised, even if just within the world of the book. We cannot suffer the same fate as the characters, our horror blunted, our tolerance for cruelty increased by overexposure repetition.

In all three cases, the compact nature of the storytelling is intrinsic to its impact. In this era of near-constant distraction, the promise of spending an hour or two with a book, rather than several days or weeks, can be attractive – but to say that was all there is to it would be selling short books, well, short. Smalls books offer much more than the opportunity for a quick read. They may be light, but they have real weight.

Further reading

You'll find even more quick reads in our guide to the best short books and novellas.