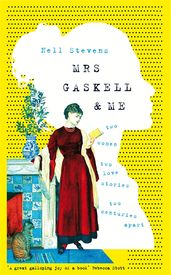

Mrs Gaskell and Me by Nell Stevens

Nell Stevens, author of Bleaker House, on why her next book will be a love letter dedicated to her 'own very special, dear friend', Elizabeth Gaskell.

Nell Stevens, author of Bleaker House, on why her next book will be a love letter dedicated to her 'own very special, dear friend', Elizabeth Gaskell.

Many of my favourite authors would be bad company in person. The book I love most in the world is Middlemarch, but I can't help thinking George Eliot might be hard work at a party. The same goes for Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who would be shy and leave early with a headache, and for Emily Bronte, who wouldn't even turn up. Dickens and Hemingway and Baudelaire would tell endless stories about themselves, and patronise the women. Jane Austen might be fun if she included the rest of us in her private jokes, but you wouldn't want to get into her bad books, and those seem easily accessible.

These two things are, and should be, unrelated: the likeability of the author, the appeal of their books. And yet, when they do come together, when you find a writer whose work moves you, and whose personality, too, strikes you as vibrant and brilliant and irresistible, it feels something like true love. That's how it is with me and Mrs Gaskell. She is my great friend in writing, in letters, in our lives lived on the page.

I had read a few of her novels before I studied her formally, and liked them. I started with Mary Barton when I was a teenager, and got through North and South and Ruth in my early twenties. It wasn't until I began an MA in Victorian Studies that I wrote about her academically; then, as I sought out material to support an essay on her bizarre little novella, Lois the Witch, I stumbled across her letters, and it was there that I truly encountered her.

Every line of her correspondence fizzes with energy. Within a single paragraph, she covers what she planned to have for dinner and an international political incident, with some literary scandal thrown in for good measure. The slapdash punctuation and multiple exclamation marks belong to a person too alive to be contained within the strictures of regular, nineteenth-century grammar. I know no other writer who can fill a page so entirely with themselves. Mrs Gaskell was witty, and cutting, and sharp, and hilarious, and gossipy, and excitable, and dramatic, and above all, brimming with love for the people around her. It oozes from those letters, that love; it reached me as soon as I began reading them, in the twenty-first century, in the Birkbeck College Library at Russell Square.

I am both possessive and evangelical about the letters. I want everyone to respond the way I do to them, but I want, also, to feel that they are mine exclusively, that Mrs Gaskell belongs to me and to nobody else. I think these are the twin impulses that informed my new book; I began by wanting to say, Mrs Gaskell is my own very special, dear friend, and to prove it, I will now tell you all about her. I think, too, that this was the motivation behind Mrs Gaskell's biography of Charlotte Bronte, published 160 years ago. Sometimes sharing the love we feel for our friends is a way of marking our territory.

Writing my book, I grabbed Mrs Gaskell by the hand and walked us through our parallel stories, she in her century and me in mine, both of us love-struck, pondering the enormity of the Atlantic that lay between us and the objects of our desire, learning how to love someone who is not with us, who may never be.

It is a book about the love of two female writers for two very different men. But it is also about the love of this female writer for that female writer, about mine for Mrs Gaskell, who is not with me, and never will be, and always will be.

Mrs Gaskell and Me

In 1857, after two years of writing The Life of Charlotte Bronte, Elizabeth Gaskell fled England for Rome on the eve of publication. The project had become so fraught with criticism, with different truths and different lies, that Mrs Gaskell couldn’t stand it any more. She threw her book out into the world and disappeared to Italy with her two eldest daughters. In Rome she found excitement, inspiration, and love: a group of artists and writers who would become lifelong friends, and a man – Charles Norton – who would become the love of Mrs Gaskell’s life, though they would never be together.

In 2013, Nell Stevens is embarking on her Ph.D. – about the community of artists and writers living in Rome in the mid-nineteenth century – and falling drastically in love with a man who lives in another city. As Nell chases her heart around the world, and as Mrs Gaskell forms the greatest connection of her life, these two women, though centuries apart, are drawn together.

Mrs Gaskell and Me is about unrequited love and the romance of friendship, it is about forming a way of life outside the conventions of your time, and it offers Nell the opportunity – even as her own relationship falls apart – to give Mrs Gaskell the ending she deserved.