Deborah Hewitt on the Finnish myths that inspired The Rookery

Visionary and mysterious, Deborah Hewitt’s novels carry currents of ancient myths. Here she tells us how pagan Finnish belief systems and deities have sparked her imagination.

Author of enthralling fantasy novel The Nightjar and its sequel The Rookery, Deborah Hewitt has a clear affinity for our feathered friends. And she also has a close connection with the mysterious world of Finnish myths and legends.

Here she explores and explains some of the mythical beliefs and characters that have inspired her: demigod Väinämöinen with his magical songs, blacksmith and inventor Ilmarinen, as well as Tuonela – the Land of Death – accessed by crossing a swirling perilous river. For the nightjar which gave Hewitt’s last novel its title, she took inspiration from the Finnish sielulintu, the mystical bird which grants and guards each person’s soul. . .

Before the eleventh century, pagan beliefs held prominence in Finland. A combination of travelling missionaries and immigration introduced Christianity to the country in the middle ages, but it was the Second Swedish Crusade that cemented its takeover. A Swedish regent, Birger Jarl, led the crusade, which resulted in Finland becoming part of already Christianised Sweden for almost 700 years. Christianisation took the form of forced baptisms along with more subtle methods, in which many of the pagan practices were allowed to continue, as long as they were practised in honour of the Christian God and not the old pagan gods. The midsummer festival, for instance, was originally called Ukon Juhla and held in honour of Ukko, the thunder God – but later became known as Juhannus, and held in honour of John the Baptist.

The original Finnish pagan beliefs were passed down orally as folklore and, with the advent of Christianity, subsequently many of these were lost. What is known of them has largely been recorded after their erasure – in part from post-Christianised secondary sources. One of these sources was Mikael Agricola’s Book of Psalms, in which he listed some of the Finnish deities and guardian spirits. Another source was The Kalevala, a 19th-century piece of epic poetry and probably the most significant work of Finnish literature. The Kalevala begins with the Finnish creation myth and tells the story of the central character, Väinämöinen, and his encounters with various Gods, heroes and villains.

The world of The Nightjar features a parallel London called the Rookery, which – in the novel – was built by Finnish refugees of magical descent, fleeing persecution from a Finland undergoing conversion to Christianity. These refugees are members of a magical race called the väki – a form of haltija, which were guardian spirits in Finnish mythology. When Alice, the main character, is introduced to the Rookery and its inhabitants, she soon encounters the descendants of the old Finnish deities and heroes – Mielikki, Ilmarinen, Pellervoinen, Ahti and Loviatar, each of whom has their own ‘House’ in which membership can be earned by those who dare take the risk.

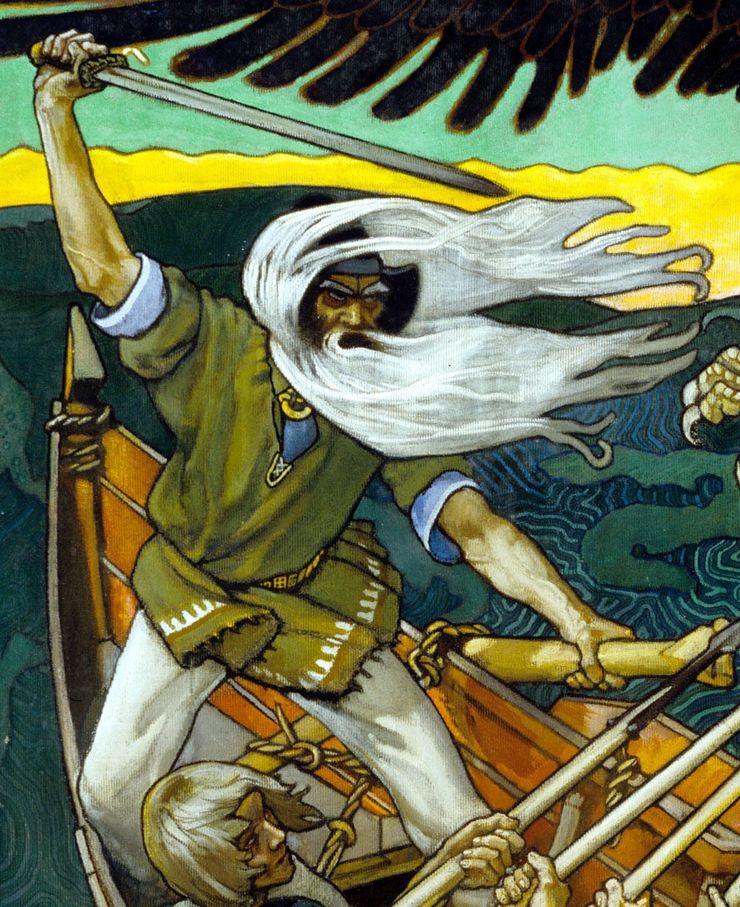

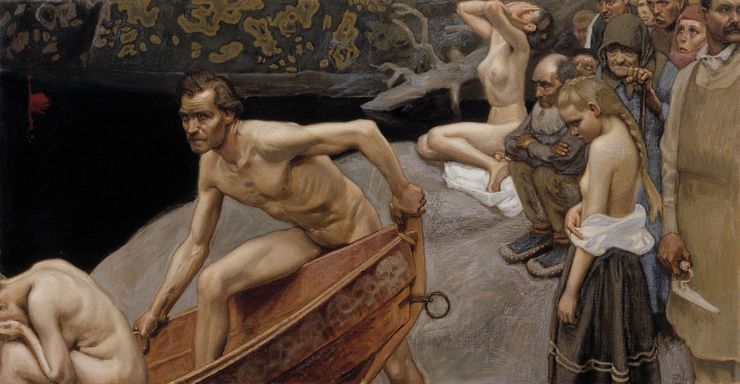

As an aviarist, Alice is gifted with the ability to see nightjars: the magical birds that guard human souls. Nightjars of course are real birds, but in the novel they are given a role heavily based on the Finnish myth of the sielulintu: a soul-bird that brings a soul to a newborn baby at birth, guards it throughout its life and takes it away at the moment of death. The Land of Death, in Finnish lore, is known as Tuonela (depicted above), though it goes by an alternative name in the novel. Death rituals, the role of birds and the concept of souls have a special place in Finnish paganism, and it’s fascinating to see the cross-over between many other belief systems. The sielulintu delivering the soul at birth, and the stork delivering a newborn baby aren’t, in the end, too dissimilar.

The Nightjar

by Deborah Hewitt

Alice has been haunted by visions of birds for as long as she can remember, but she has never known what these mysterious birds are, or what they might mean. That is until she meets Crowley, who appears at her door and tells her that she has been seeing nightjars, the miraculous birds which guard our souls. . .

Forced to go on the run, Alice follows Crowley to an incredible alternate London known as The Rookery, to hone her talents. But can she trust him? Alice must risk everything as she navigates a dangerous world of magic, marvels and death cults.

The Rookery

by Deborah Hewitt

When Alice discovers The Rookery, an alternate London, she enters a new world where she can see nightjars, the guardian bird of the soul. This sweet magic has a dark side though, one that threatens both Alice and her friends. Under attack from mysterious forces, Alice dives into a realm of magic and danger to uncover the conspiracy. It transpires that the Rookery itself is in peril, and Alice may have to pay a high price to save it.