MY KINDA SCENE: David Gibbins on Master and Commander

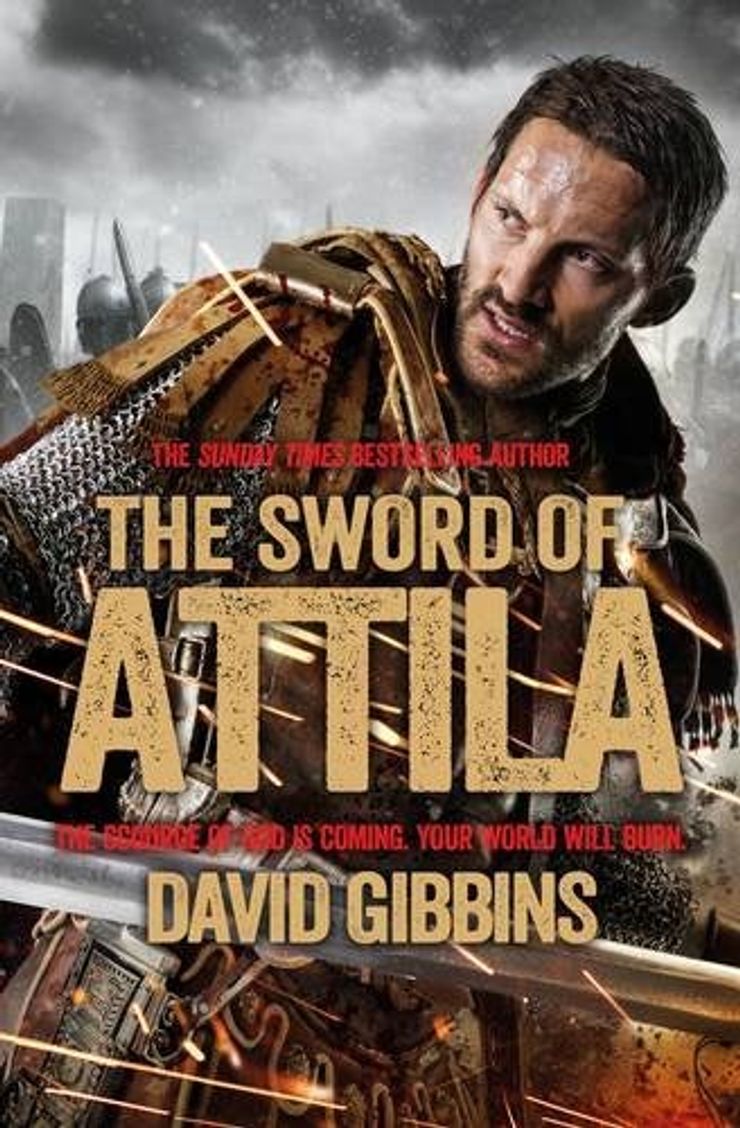

David Gibbins is the author of ten novels, and his most recent - The Sword of Attila, based on the hugely popular Total War video game of the same name - is out in paperback right now.

As well as writing excellent historical fiction books that have sold 3 million copies and been translated into thirty languages, David takes his swashbuckling very seriously. He recently dove to the wreck of a Royal Navy frigate and fired a Sea Service flintlock pistol (see pic), both dating from 1805, which also happens to be the year his favourite film Master and Commander is set.

Below he tells us his favourite scene . . .

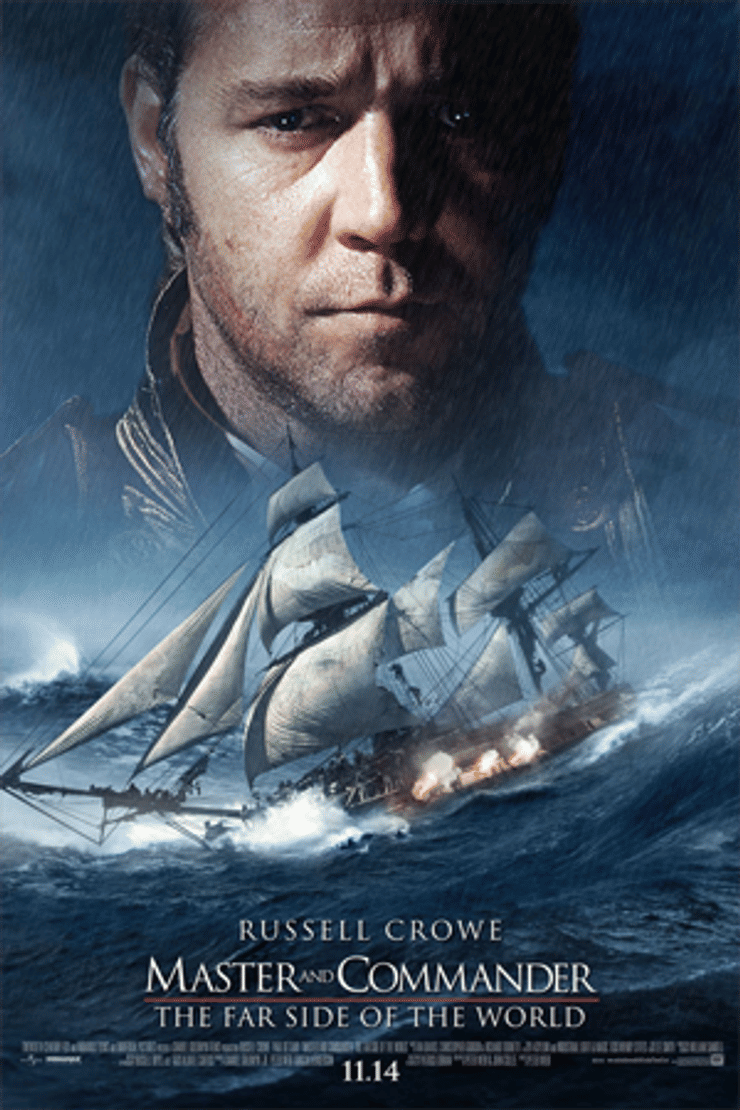

My favourite film of all time is Peter Weir’s Master and Commander, based on Patrick O’Brian’s brilliant series of seafaring novels set during the Napoleonic Wars. In the film we follow Captain Jack Aubrey, ‘Lucky Jack’, as he takes HMS Surprise down the coast of South America and into the Pacific, chasing the elusive French frigate the Acheron. Jack’s friendship with Stephen Maturin, the ship’s surgeon – their love of music, their sometimes conflicting sense of duty and purpose, their companionship in arms when called to action – is beautifully played by Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany, in a film unsurpassed in this genre for the attention to historical detail, and for a vision that superbly captures the adventure and excitement of seafaring in the age of sail.

We learn that Maturin is not just a surgeon, but also a passionate naturalist – we see him with twists of paper stuffed into his ears poring over his specimens while the guns practice overhead. The fictional voyage of Surprise almost exactly prefigures the actual voyage some twenty-five years later of Charles Darwin in HMS Beagle, a parallel that becomes even more apparent as Surprise rounds Cape Horn and heads towards the ‘Enchanted Isles’, the Galapagos, a staging post in Jack’s search for the Acheron but also a watering stop where he will allow Stephen a few days’ exploration, ‘subject to the requirements of the Service.’

The scene I love most takes place just as the ship reaches the islands. To the accompaniment of Yo-Yo Ma playing Bach’s Prelude from the Unaccompanied Cello Suite No 1 in G Major - music perfectly chosen for the moment, the building crescendo matching the rising emotions of discovery – we see Maturin at the ship’s rail beside himself with excitement, having just spotted a new species of flightless cormorant. His young assistant sees a swimming iguana. ‘Iguanas don’t swim,’ Maturin says. ‘They’re land animals.’ He takes up his spyglass, and sees it for himself. ‘Well I’ll be damned. Two new species in as many minutes.’ In Maturin’s eyes we can see the extraordinary possibilities that he now knows could lie ahead of him. But we also know, as he does, that recording ‘inestimable wonders’ can only be incidental to their purpose, and indeed to his own duty as a ship’s officer. On the opposite side of the ship Jack stands resolutely with his back to the islands, staring out to sea in his search for the Acheron. In that instant we know that Stephen will miss his ‘Darwin moment’, if only by a whisker.

That scene beautifully captures the dichotomy within their friendship, a driving force of the film. In the event, after a first attempt to pursue the Acheron, Aubrey does decide to return to the Galapagos – though only because Stephen is accidentally shot and needs to recover on land (leading to another superb scene where Maturin operates on himself, and enlists Jack’s help, ‘that is,’ he squints at Jack through the pain, ‘if you have the constitution for this kind of thing’; ‘My dear doctor. I have been amongst and around wounds all my life,’ Aubrey replies, sweating and looking pale). Later, hobbling across the island, having spied the elusive cormorant again, it is Stephen himself who spots the Acheron and – officer first this time, naturalist second – realises he must report the discovery as soon as possible to Jack, even if it means abandoning his specimens in his haste to return. The cages are opened, and the birds he has collected escape – Darwin’s finches, perhaps, flying away with the revelation that was so nearly within Stephen’s grasp?

At the end of the film, having fought side-by-side in the capture of the Acheron and having sent her off with a prize crew and the prisoners, we see Aubrey and Maturin together in the captain’s cabin tuning up their instruments. Jack has promised another return to the Galapagos now that their mission is over. But something Stephen says makes him realise that the captain of the Acheron, thought to have been killed, must be among the prisoners. Jack changes his mind: he must follow the Acheron and escort her into port. ‘Beat to quarters’, he orders. Maturin, downcast with the map of the Galapagos in front of him, looks resignedly at Jack. ‘Subject to the requirements of the Service’, he says. ‘Ah,’ Jack replies, seeing the map. ‘Well, Stephen. The bird’s flightless?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Then it’s not going anywhere.’ Jack smiles, Stephen sighs and they strike up a beautiful Boccherini quintet while the camera pans out to the ship becoming a small speck on the ocean. Like much of the best fiction, like life itself, loose ends are left untied, possibilities that are hinted at still remain ahead, and the joy for those of us along for the ride – whether watching the film or reading the novels - is in the voyage more than the destination, with the Enchanted Isles always lying just beyond the horizon.