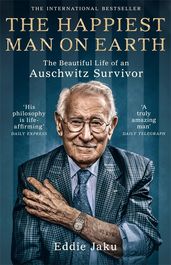

3 lessons I learnt from Eddie Jaku, survivor of Auschwitz

In these strange times and sometimes challenging times, the insurmountable resilience and kindness of a man who experienced one of humanity's darkest hours brings the hope and lessons we all need.

The books that have left the greatest impression on me are those that made me feel anew the warmth of the bed I was (invariably) reading in. They are those that made me feel a rush of affection for the person sleeping next to me, and gratitude for the sound of their slow, unencumbered breathing (or snoring) – indulgent in their sleep because they were, above all else, completely safe. Small, blissful things that, in fact, if I didn’t have them, wouldn’t be so small at all.

A few nights ago, I’d been offloading to – or rather, on – my partner about some financial worries. We’re at the simultaneously brilliant yet financially draining whirlwind of our late-twenties-early-thirties in which swathes of our friends are getting married in close succession, made closer still in the wake of Covid now that so many have been rearranged. It was 11.30 p.m., and the magical hour that my anxiety finds its energy and my long-suffering partner loses his.

I relented and turned to reading to quiet my ‘busy brain’, as I’ve taken to calling it, and I began Eddie Jaku’s memoir: The Happiest Man on Earth. Chapter One: Money isn’t everything.

Sometimes, fate reaches out a hand and firmly but fairly, like a rattled grandmother, clips your ear.

Eddie Jaku was born in Leipzig in 1920. In his own words, he and his family considered themselves ‘Germans first, Germans second and then Jewish.’ But in 1933, as the Nazi regime tightened its grip around Germany, at the age of just thirteen, as a Jew, Eddie was no longer able to study, and he was forced to assume a false identity of orphan Walter Schleif and attend a school nine hours away by train. When he returned for the first time five years later, hoping to surprise his parents on their twentieth wedding anniversary, he found his family home empty. That night, which would be remembered as Krystallnacht, Eddie was savagely beaten, his beloved family dog killed, and the house that had been home to his family for generations, destroyed. The next day, Eddie was sent to a concentration camp for the first time, and his life was changed irrevocably.

I stayed up until 2 a.m. reading that night, turning pages as Eddie paced through his life, through stories of friendships, of escape after escape, of unimaginable resilience, unexpected kindnesses and unfathomable cruelties, leading ultimately to Auschwitz, and beyond. The book is now dog-eared by the sheer number of pages I turned down in hope of remembering the words written there, and here are just a few of the lessons I took from those pages, that I’m particularly grateful for in the strange chasm of a year that is 2021.

I take my family for granted

All of our families are different; different in structure, certainly different in quirks. Some are the family that we are born with, others are the family that we have chosen. For me, it’s a wonderful mixture of both and I know that most days, I take them for granted even when I try not to.

We get caught up in work, in schedules, in the weekly shop, and we rush from life commitments to social commitments without taking a breath. But how wonderful to have events to rush to and from. To have a friend waiting in a cafe to see us, or a sister waiting at home, or a phone full of unopened messages that we need to reply to – not because we have to stay on top of the never-ending life admin that now includes our WhatsApp – but because there are real people we love at the other end of those messages, that care about how we are.

After reading Eddie’s account of losing his beloved and brave parents, Lina and Isidore, I took the time to tell the people around me just how much I love them.

‘I did not get a chance to say goodbye to my beloved mother, and I have missed her every day of my life. Every night, I still dream of her, and sometimes wake up calling out to her. When I was young, all I ever wanted was to be back with her, to spend time with her, to eat the challah she made on Friday afternoons, to see her smile. And now, I never would again. She would never smile again. She was gone, murdered, stolen from me. There is never a day I do not think that I would give everything I have to see her just one more time. If you have the opportunity today, please go home and tell your mother how much you love her. Do this for your mother. And do it for your new friend, Eddie, who cannot tell it to his mother.’

The part you play is important, even if you don’t think it is.

What if, when we grow up, we don’t become the astronaut, the doctor, the lawyer? What if we’re not the one giving the TED talk, we’re the one in the audience trying and failing to quietly open the snacks? At some point, our careers became a defining point of who we are, and to some extent, how we value ourselves. Perhaps it was all in the phrasing of the perennial question: ‘what do you want to be when you grow up?’

‘I had learned early in life that we are all part of a larger society and our work is our contribution to a free and safe life for all. If I went to a hospital and saw instruments that I had made and knew that they were being used every day to make life better, this gave me great happiness. The same is true of every job you do. Are you a teacher? You enrich the lives of young people every day! Are you a chef? Each meal you cook brings great pleasure into the world! Perhaps you do not love your job, or you work with difficult people. You are still doing important things, contributing your own small piece to the world we live in. We must never forget this. Your efforts today will affect people you will never know. ’

Eddie’s words resonated with me as a beautiful way to look at the world, the part we play in it, how we find purpose in what we do and crucially, how we appreciate the contributions of others. What if we placed less value on the individualistic view of what we do, and instead took pride in how what we do affects others? Something to remember when you’re next buried in emails and wondering if what you do matters, because it does.

History repeats itself – and we still haven’t listened to it

This may seem obvious, but Eddie’s perspective on life shifted how I want to respond to my frustrations at the world.

In the last few years, the notion of history repeating itself has felt prophetic. The world once again finds itself politically and ideologically divided. So-called politicians make scapegoats of marginalized communities and races, and in 2020, there were nearly 80 million people who have been forced to flee their homes. In 2019 the UN reported that global refugee figures were at their highest since World War Two. One can’t help but be struck by the similarity between Eddie’s story, which began in 1938, and Behrouz Boochani’s story, which began in 2013.

Eddie Jaku has endured the worst that humanity can inflict. And yet, despite this, Eddie navigated unimaginable circumstances with kindness, compassion and empathy for those around him.

If we’re truly going to learn from history and those that endured it, we need to listen to those that implore us to find, and fight for, common ground (even when it seems impossible). We need, like Eddie, to hold compassion, kindness and empathy above all else.

‘Here is what I learned. Happiness does not fall from the sky; it is in your hands. Happiness comes from inside yourself and from the people you love. And if you are healthy and happy, you are a millionaire. And happiness is the only thing in the world that doubles each time you share it. My wife doubles my happiness. My friendship with Kurt doubled my happiness. As for you, my new friend? I hope that your happiness doubles too.’

We know the importance of gratitude, how this can transform our day-to-day enjoyment of what is. But Eddie’s story is as much a lesson in perspective as it is a lesson in gratitude, which in a year that has presented its fair share of challenges, is absolutely the reminder I needed, and one that we all do from time to time.

While I’d like to think of myself as a person with perspective on my own issues, and equally as one that also knows that it’s important not to minimise our own suffering – after all, that way madness lies, right? But reading Eddie’s memoir didn’t bring a sense of shame for feeling hopeless on difficult days or overcome by 21st-century stresses (2022 really outdid itself on that front). Instead, it filled me with a sense of immense comfort in an almost tangible gratitude, complete admiration for what incredibly special people like Eddie can endure.

Who would have thought that in these strange times , a memoir of one man’s experience of one of humanity’s darkest hours would be exactly what our headspace needs. Yet, thanks to the insurmountable resilience, hope and kindness of the man who wrote it, I can assure you that it is.

I went to sleep that night feeling not only incredibly lucky, but hopeful. Which is testament only, to Eddie.

‘This is the most important thing I have ever learned: the greatest thing you will ever do is be loved by another person.’

— Eddie Jaku

The Happiest Man on Earth

by Eddie Jaku

This heartbreaking yet hopeful memoir shows us how happiness can be found even in the darkest of times. In November 1938, Eddie Jaku was beaten, arrested and taken to a German concentration camp. He endured unimaginable horrors for the next seven years and lost family, friends and his country. But he survived. And because he survived, he vowed to smile every day. He now believes he is the ‘happiest man on earth’. This is his story.